Am I a planner--that is, do I plan out my novels in advance? Or am I a pantser--that is, do I just come up with a character and setting, situation, or problem and start writing and see what happens? I'll answer that question by the end.

|

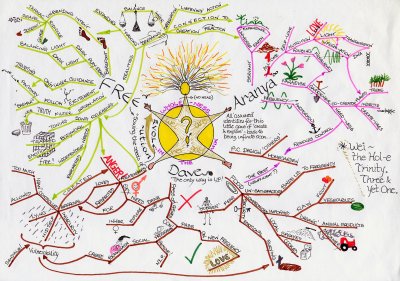

| Mindmap, from Wikipedia Commons |

There are those passionate from each camp who can turn this into a loud debate. The pantsers (the term comes from writing "by the seat of the pants") can't imagine how you wouldn't get bored knowing in advance what's going to happen. The planners (aka plotters) can't imagine how you'd have anything like a novel at the end of 60,000 words of unplanned writing about a character's life. You'd have 60,000 words, they admit, but wouldn't it be something of a mess? The debate can escalate into an online dust-up in no time at all--which seems a bit silly to me.

Some genres seem more geared to one style or the other. While there may be a few pantsers among classic mystery writers, I suspect it's very few. There's so much to structure in a mystery--red herrings, plants, reveals, when the actions of the various actors occur versus when the sleuth finds them out--that it'd take some genius or structural savant to keep that all straight as she invented it and make it thrilling for the reader. On the other hand, a literary novel of self-discovery might work just as well without a writing plan.

If an author is to write in a plotted genre--which includes mystery, thriller, high fantasy, space opera, adventure, western--she'll have to arrange events in her novel to best effect at some point. That could be before she starts or between first and second drafts. Some pantsers even call the first draft the "discovery" draft, for they discover while writing what the book will be about, and then they start anew on the second draft with a plan in mind, using very few of the pages written in the first draft. Arranging events within a novel for increasing tension, and in logical order, is part of the task of the novelist. Unless she's writing stream of consciousness or experimental novel, it has to be done sometime. Pantsers generally need a draft more than planners before they achieve a finished novel.

An author might not have to plot in advance, on paper, if she writes a formulaic sort of book. Contemporary romances and westerns have a structure that is easy for a genre writer to internalize. The plotting has been done at some point in the writing process (or indeed years before the writer was born), so for each novel, there's no need to reinvent that wheel. Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey, re-envisioned for writers by Chrisopher Vogler here and in his book, is another sort of general plan. This can work well for coming of age stories, high fantasy, and first novels in thriller series, among other genres. It wouldn't be difficult to memorize that structure. Several screenwriters have internalized the three-act structure. And so a number of writers have a plan of sorts--even if they don't write it down in outline form--before they begin.

Planners use various methods to organize their ideas. Some draw mind maps. Some make a bullet-point list of major plot points. Some fill out twenty-page character interview forms. Some use the snowflake method, which starts with a one-sentence summary and builds it up to a bullet-point list of major scenes and then a complicated list of all scenes and then a summary of each scene, and then to the novel text itself. Others use unusual plans: they mock up a movie trailer first, perhaps, or paint a mural. Here are nine famous novels' plans. There are no rules here. "Whatever works for you" is the best advice there is, here.

Few plotters stick slavishly to their plans. In my novel Quake, for instance, I had another three viewpoint characters planned, each in a different location, but McKenna and Haruka, intended to be minor characters, won me over, and I tossed those others out to make room for the two girls. This resulted in my sticking to the events in one town, which made it a different novel than the one I had planned. Only the two main characters and the earthquakes stayed the same. Like most planners, I understood: the plan doesn't control the writer; the writer controls the plan.

|

| Fraction of my Excel plot chart for the R Sparks Gothic, Mists of Seacliffe |

And so I've revealed that I am a plotter. I use either a bullet-point plan for major scenes or a spreadsheet plan for all scenes, but I keep it flexible so that good ideas that arise during drafting can be fit in, too. Yes, I'm a planner--but that's descriptive, not prescriptive. Every writer should do what works for her.